For many dog guardians, nothing beats watching their dogs bounce around and wrestle with another dog. But have you ever watched two dogs play together and wondered, “what the heck is happening?!” You wouldn’t be the first to ask that question! In fact, there is a growing body of literature on the science of canine play , and as it turns out, doggy play is incredibly complex and intricate: it may look like tackle football, but it’s actually more like chess. Read on to learn more about why dogs play with each other; what healthy play looks like; red flags during play; and tips for encouraging good play between doggy pals.

What Does Science Say About Why Dogs Play?

There are many different styles of doggy play, and it can look different depending on the the individual dogs, but dog-dog play is characterized by natural canine behaviours, such as stalking, hunting, or fighting, performed out of context. For example, during play one dog may chase another dog (a part of the predatory sequence!) but the dog is not actually trying to catch and take down the other dog. In other words, there is no true intent behind the behaviour. An easy way to think about this is to imagine the dogs are playing make-believe: they are practicing real-life skills in lighthearted, unserious scenarios.

In her article about why dogs play, author and dog-behaviour expert Zazie Todd, PhD, reviews some of the scientific literature about play in dogs. She summarizes that:

“Ultimately, dogs play because it helps them learn motor skills, build social cohesion and prepare for unexpected things to happen so they can cope better when they do. Different stages of play may have different functions, with the beginning and end of a play bout especially important for social cohesion, while the main part of play is most important for learning motor skills and preparing for the unexpected.”-Zazie Todd, PhD

Dogs and puppies use play to practice communication and build social skills: through play, they learn what’s appropriate vs what’s not; how to signal intent to other dogs (e.g. how to invite the other dog to play, how to ask for space) and how to read and respond to other dogs’ signals. Dogs and puppies also learn important motor skills through play, that is, how to move their bodies in different ways; how to-self correct when they lose their balance; and, importantly, how much biting/mouthing is too much (what we call bite inhibition). Todd also mentions that play helps dogs learn resilience, or how to to cope with unpredictability and real-life stressors.

There are also evolutionary purposes of play : play is often a way for animals to learn and practice essential survival skills. Puppies, through play, practice hunting, chasing, and biting behaviours. And because dogs are social animals, they have the capacity to form strong bonds with each other; play is one way they reinforce social bonds, building trust and learning the “rules” of interaction. From an evolutionary perspective, these social bonds are important to survival: dogs who have learned to communicate effectively with each other are more likely to avoid costly and dangerous fights with each other!

Benefits of Play

Understanding the “why” behind dog-dog play helps us better understand the many benefits of healthy, happy play between dogs. Some of these benefits are listed below:

- Stress Relief: Just like humans, dogs use play to manage stress. Play helps them let loose and feel comfortable in their environment.

- Mental Stimulation: Dogs are intelligent creatures, and play is one way they learn to problem-solve (again, think of play as a game of chess!)

- Mood Enhancement: Engaging in play releases endorphins, which contributes to a dog’s overall happiness and can sometimes reduce negative behaviours like chewing or barking excessively.

- Learning Boundaries: Through play, dogs learn when they are being too rough or too soft, helping them develop appropriate play behaviour.

- Developing Communication Skills: Dogs learn to read each other’s body language, which is crucial for play and overall social behaviour.

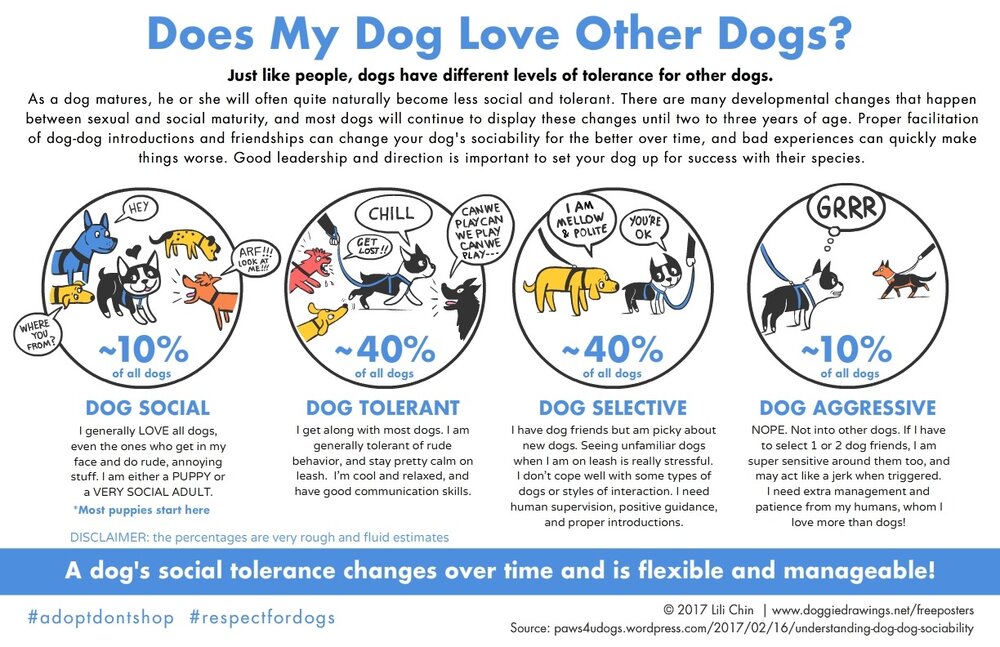

Note that while dogs are social animals and play is an important part of social learning and bonding, there is a dog social spectrum : some dogs love to play with other dogs; some are selective; some do not enjoy the company of other dogs. As dogs age, they typically (though not always) become more selective/picky about playmates- this is normal! Below is a helpful infographic that describes the canine social spectrum.

Green Flags: What Does Good Play Look Like?

Clearly, play between dogs has many benefits. But not all play is appropriate play! Below is a list of signs (what we call meta-signals) that play between two dogs is happy and healthy.

- Equal Play/role reversal – play should be approximately equal between the two dogs. They should take turns chasing, pinning, mouthing, etc., and their body language should mirror each other. They may turn their bottoms towards each other and curl around each other as well

- Frequent Breaks: frequent breaks are an absolute must for healthy play, otherwise things can get too intense, too fast. Play that goes on for longer than 30 seconds- 1 minutes without a break is a red flag. (Breaks can be as short as 2-3 seconds: puppies may separate from each other briefly before going back for more). Some dogs don’t know how to take breaks, so breaking up the play every 1 minute or so and then seeing whether both dogs want to go again (this is called a “consent test”) is a good way to help puppies learn that breaks are good.

- Play Bow: One of the most recognizable play signals, the play bow (where a dog stretches its front legs and lowers its chest) invites another dog to engage and communicates playful intent

- “Play face”: the dog’s jaws are loosely open and relaxed, their tongue may be lolling out to the side. Many people observe their dog’s face looking “goofy” or “silly”

- Bouncy Movements: Exaggerated movements, like bouncing, signal a playful mood and show the other dog that no harm is intended. Body language should be loose and wiggly. When they run, they should resemble a rocking horse- bouncy

- Mouthing, Barking, and Chasing: Light bites or mock chases are natural play behaviours that dogs learn early on. Some dogs like to make noise during play, and that’s ok! Again, watch for other signs of healthy play (frequent breaks, loose wiggly body language, etc.)

- Dogs Frequently Turn and Face Each Other (especially during chase- this helps them check in with each other and ask for space if needed), and listen when the other dog asks for space

- Self-handicapping: the dogs inhibit the intensity of certain behaviours, and will allow their playmate to temporarily “overtake” them. Self-handicapping demonstrates that the dog knows how to adjust her ability, size and strength to meet the needs of her playmate

Now that you know some signs of good play, here’s a chance to put your observation skills to the test! Below is a video of my two male border collies, Mack and Hamish, roughhousing in the yard. The play is loud and at times seems pretty violent- yikes! But watch closely: what meta-signals from the list above do you see?

Red Flags: What to Avoid During Play

Rough, loud play can be healthy and normal for many dogs. So how do we know when play becomes inappropriate? Below are some red flags to watch for.

- Escape or avoidance tactics: if one dog runs and hides behind a human, under a chair or bench, behind a tree, etc, they are asking for space.

- Group chase or 2-on-1 play: dogs do not like to feel like they’re being ganged up on. The safest and best play is usually 1-on-1.

- Yelping: This is a clear sign that a dog has been hurt

- Lack of breaks: this is arguably the biggest sign of unsafe play. If the play continues without any breaks, it is likely to increase in intensity. Separate the dogs and let them have a break

- Escalating growling, barking, or other vocalizations: some vocalization is normal, but watch for increases in volume, frequency, and duration

- Hard staring: if a dog’s mouth is closed and they are staring intently without looking away, that’s a clear sign that he does not want to play or engage

- Stiff, tense body language and slow, stalky movement

- Body slamming: this behaviour can cause injuries and is dangerous; it is often a sign of over-arousal

- Relentless chasing with no role reversal or self-handicapping

If you notice any of these red flags during play, break up the dogs immediately. Do not let the dogs “work it out on their own”. Many dogs, particularly young puppies, need a little guidance to learn good play skills, so why not help them out?

Help! My Dog is Too Rough: Tips for Encouraging Good Play

- Hire a certified professional trainer if you’re concerned or have questions. A trainer will be able to assess your dog’s play style and help foster good play, and they also may be able to match you and your dog with another dog with a similar play stye.

- Consent tests: If you are ever concerned about whether the play you’re observing is good or bad, break the two dogs up, feed them a treat, then release the dog who was showing signs they were uncomfortable during play. Do they go back for more? If yes, release the other dog. If no, best to keep the dogs separate.

- Choosing appropriate playmates for your dog: many dogs are selective about who they like to play with (see the doggy social spectrum above). If this sounds like your dog, I recommend avoiding off-leash parks and instead setting up individual playdates for your dog with a like-minded playmate. Choose a dog similar in size and with a similar play style.

- Know your dog’s play style: every dog has a different play style! Learn what is normal for your dog. For example, it is normal for my dog Mack to growl, snarl, and bark during play so I don’t worry about it. I would worry if my other dog, Hamish, growled during play- that’s not normal for him!

- Choose appropriate places for play: small enclosures can create tension because dogs feel trapped and obligated to engage with each other. These spaces make it hard for dogs to take breaks and decompress in between play sessions. Instead, choose larger greenspaces (the more places to stop and sniff, the better!) so the dogs can easily disengage and do something other than play. Big open fields, walking trails, beaches, and/or wooded areas are your best bet.

Play serves many functions and is an important part of social and motor development for our 4-legged friends! Play involves complex communication between play mates and although it can look rough-and-tumble and be loud, there is lots of learning and signalling going on under all that ruckus. Does your dog enjoy playing with other dogs? What’s their play style like? Do they have a signature wrestling move?

About the author: Beth Dowbiggin is a professional dog trainer, a Karen Pryor Academy Certified Training Partner (KPA-CTP) and a Certified Family Dog Mediator (FDM) living and working in Prince Edward Island, Canada. She teaches puppy, basic manners, and advanced obedience classes through Spot On Dogs in Charlottetown. She has two border collies, Mack and Hamish.